What is LWOP?

Life without parole, or “LWOP,” is a sentence to remain in prison until you die. If you have LWOP in the United States, you’re condemned to prison for the rest of your life, with no opportunity for release. Some call it the slow death penalty, or death by incarceration. Juvenile LWOP, or “JLWOP,” means a person was under age 18 at the time of a crime that resulted in an LWOP sentence.

It hasn’t always been this way.

Today’s definition of life without parole is a historical anomaly. For most of LWOP’s history, the sentence carried a reasonable possibility of release. A person with the sentence might never get out, but there was still the possibility of parole.

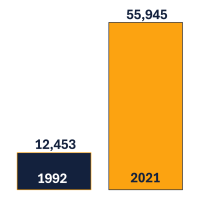

That began to shift in the 1970s when the scope of the sentence changed—from a sentence with the possibility of a second chance to one with no chance. The use of the sentence also dramatically skyrocketed, and not only for people convicted of murder: The sentence is used in some US jurisdictions for lesser crimes, such as robbery, aggravated assault, kidnapping, and even nonviolent drug offenses. Increasing sentences with no possibility of release led to a predictable result: Between 1992 and 2021, the LWOP population in the United States rose from 12,453 to 55,945, a whopping 350 percent increase.

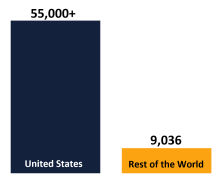

The United States is an outlier.

LWOP sentences are virtually unheard of in the rest of the world with the US holding a shocking 83 percent of the world’s LWOP incarcerated population. The more than 55,000 people sentenced to LWOP in the US far exceeds that of any other nation—in 2019, Kenya was second with just under 3,700 people. Additionally, in complete disregard of international human rights standards, the US is the only country that subjects children to the harsh sentence.

The US LWOP population

had a 350 percent increase between

1992 and 2021:

had a 350 percent increase between

1992 and 2021:

The US holds 83 percent of the world’s LWOP population:

Top three US states with the most LWOP sentences:

Florida: 10,438

Pennsylvania: 5,375

California: 5,134

How is LWOP harmful?

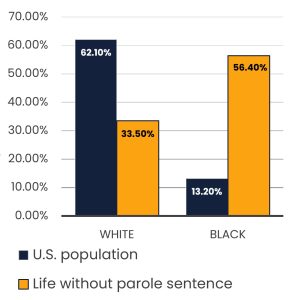

Racial Injustice

Life without parole sentences disproportionately affect people of color. This is due to a number of factors, including racial bias within the criminal legal system, inadequate legal representation, and mandatory sentencing laws that limit judges’ discretion. Even if convicted of similar crimes, Black people are more likely to be sentenced to LWOP than white people1. A 2023 study states, “Racial and ethnic disparities are readily apparent in criminal sentencing data and grow with lengthier sentences. More than half (55%) of all people serving LWOP in 2020 were Black.” These sentences deny individuals the possibility of rehabilitation and reintegration into society, leading to a perpetuation of the cycle of racial inequality.

Racial Disparity in LWOP

Graphic adapted from Alison Walsh, “The Criminal Justice System is Riddled with Racial Disparities,” Prison Policy Initiative, August 15, 2016.

Financial Harm

When states choose to allocate significant resources to incarcerate individuals for the duration of their natural lives, it inevitably reduces funding available for services known to help reduce crime, such as education, programs for youth, substance use support, job creation, and mental health care.

Aging Out

It is a well-recognized fact: as people get older, they become less likely to commit crimes. Research shows that the highest risk of committing crime occurs under age 26, after which there is a steady decline. Sentencing people to life without parole ignores the reality of “aging out” of criminal behavior, and the increased likelihood of rehabilitation.

Loss of Contributions to Society

When people are locked up, they can’t contribute to the broader community. A survey of over 100 people who once were sentenced to LWOP in California but have since been released shows that:

- 88 percent are working, with the vast majority of that number working full-time (40 hours per week) or more.

- 94 percent have volunteered in their communities since being released.

- 84 percent are assisting family or friends financially or in other ways, like caring for sick or elderly people.

Sources

[1] Ashley Nellis, “No End in Sight: America’s Enduring Reliance on Life Imprisonment,” June 23, 2021, https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/no-end-in-sight-americas-enduring-reliance-on-life-sentences/.

[2] This number was calculated by multiplying the national average annual cost per inmate ($34,540) [3][i] by the total number of individuals serving LWOP in the United States (56,000) [ii]. It is important to note that this number does not represent the total annual cost savings of releasing every person sentenced to LWOP, as fixed prison spending would remain. This number simply reflects a conservative and simplified attempt to measure the exorbitant costs associated with life imprisonment.

[3] This figure is the average cost which is a broad estimate created by dividing annual total spending on prisons (including labor, electricity, construction, and other fixed costs) by the annual total number of inmates [ii]. It is different than the marginal cost, which is the actual direct cost of a single prison admission or release, which doesn’t affect most fixed costs. Both average and marginal costs vary widely by state. Additionally, the average annual cost per LWOP prisoner is likely significantly higher than this estimate due to the increased cost of caring for an aging population.

[i] “2019 National Averages,” National Institute of Corrections, August 17, 2021, https://nicic.gov/state-statistics/2019.

[ii] Ashley Nellis, “Nothing But Time: Elderly Americans Serving Life Without Parole,” June 23, 2022, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/nothing-but-time-elderly-americans-serving-life-without-parole/.

What About Survivors?

Trino, a man whose brother was murdered, speaks with Kiilu, who was convicted of murder at age 18 and spent 27 years in prison.

Survivors of crime have wide-ranging, diverse perspectives on punishment. Their opinions on justice are important, but often get relegated to stereotypical and oversimplified assumptions. It is not uncommon for the public to wrongly assume that survivors of crime want only one thing: retribution. Some tough on crime advocates perpetuate this idea by equating retribution with “closure,” suggesting that harsh punishment will somehow end grief for the loss of a loved one who was murdered. However, research shows that most survivors believe closure is not possible, and for many, it is not the goal. Commonly, survivors seek justice beyond the outcome in their personal case, and are focused on justice for future generations, communities, other survivors, and even for those who commit acts of violence.

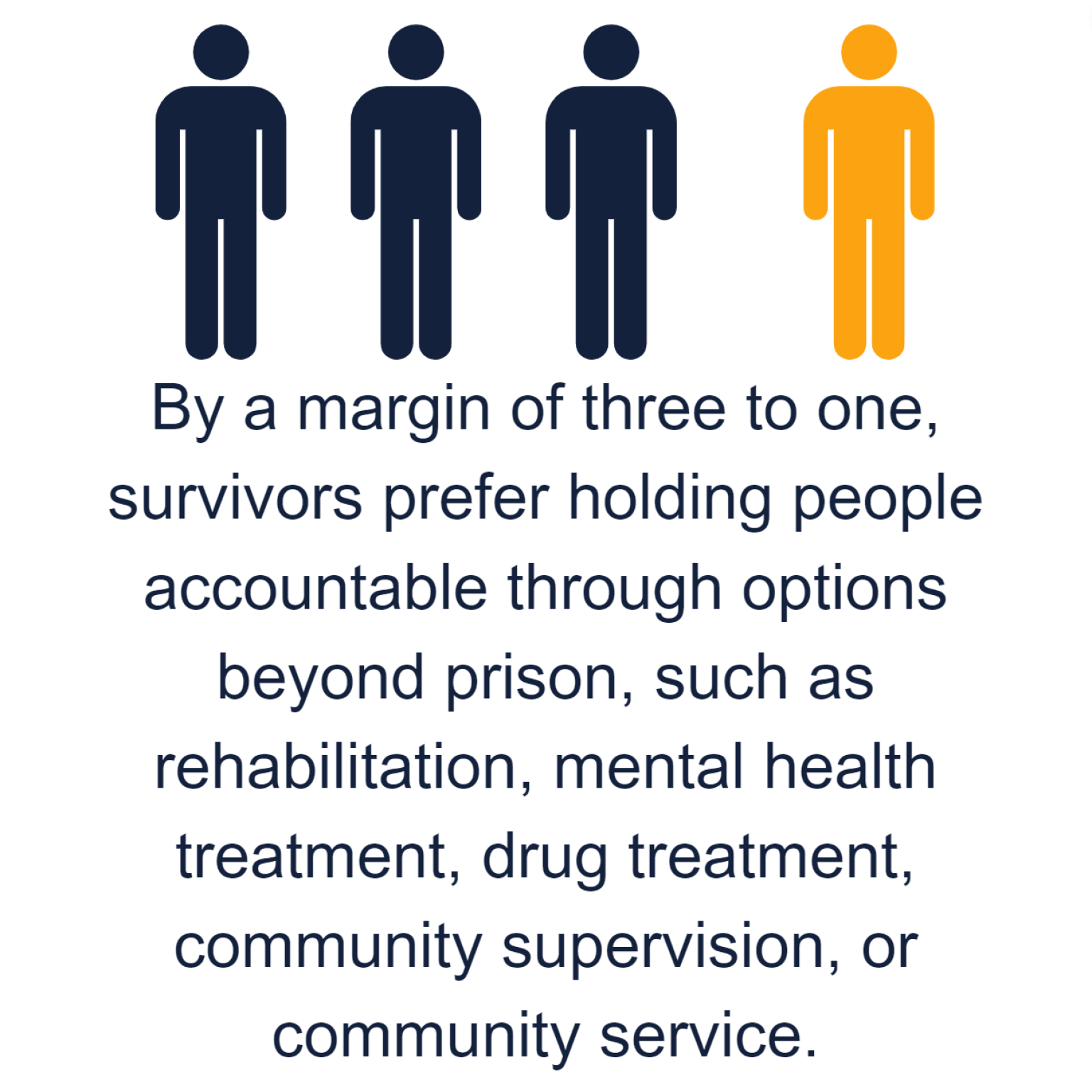

The first-ever national survey of survivors’ views on public safety in the US found that six in 10 survivors of crime prefer shorter prison sentences and more spending on prevention and rehabilitation. That study also revealed that, by a margin of nearly three to one, crime survivors believe prison makes people more likely to commit crimes than to rehabilitate them. Further, by a two to one margin, survivors prefer that the criminal legal system focus more on rehabilitating people who commit crimes than punishing them.

Most survivors believe justice means state dollars are better spent on rehabilitation and prevention than on life without parole sentences, and that second chances enhance the justice system and communities.

Some people who have survived the murder of a loved one have come to believe that the sentence of life without parole is wrong.

“I don’t believe in capital punishment, and I think that life without parole is worse than the death penalty. We all have love and the lifeforce in us. I don’t want the man who killed my daughter to never have a chance to be released.”

"I would champion anyone to come home as long as they are truly transformed. I have seen the effective side of rehabilitation and lives are truly being transformed because rehabilitation is being offered. To those who haven’t transformed: there’s no hiding. The system is watching your behavior, there are write-ups. Actions and the life someone is living while in prison tells the truth about a person."

"I don’t agree with life without parole. I believe that the decision about whether someone gets out should be made on a case-by-case basis. How is that person displaying change? What actions are they showing to me or the board that they have rehabilitated themselves? The decision should be based on the actions of the person that prove if they have changed. Because I am a mom, I feel that if the person who killed my son can show the steps he took to become a better person and the actions that show he has changed, then I will be fine with him getting a chance."

"I think that people can change. At the trial, the man who killed my nephew, he didn't even seem to care. Now, so many years later, it would be interesting to see who he has become. If he's still the same, I wouldn’t want him to get out. But I think a no-parole sentence could make people give up and not try changing, and we should help people not give up. If they know they have a chance, I think people might change. I think the sentence should be 25 years, and then we see."

There are Alternatives to LWOP

Accountability.

Community Safety.

Personal Transformation.

Community Safety.

Personal Transformation.

There are effective alternatives to life without parole.

States can impose sentences that hold people accountable for their actions, ensure public safety, and encourage and recognize personal transformation. Some alternatives are:

Return to the way many states once used LWOP

The meaning of LWOP has changed since the early-to-mid twentieth century: It once meant that there would be an opportunity to earn release after being incarcerated for a set period of years. For example, in Pennsylvania, it was 15 to 20 years, Louisiana was 10.5 years, and California 12 years.

An opportunity for parole is not a guarantee of release. A state can impose a sentence that ensures appropriate minimum prison time for punishment, after which a review can assess rehabilitation. People who do not rehabilitate are not paroled and could end up serving the sentence for life.

Create more equitable opportunities for release

To ensure proportionality among sentences, create geographic uniformity across a state, and build a system that incentivizes rehabilitation, states can require review and the possibility of release in all sentences. If a person with a lengthy sentence knows they will have the chance to prove they are suitable for release after a set number of years, they are more likely to choose to begin to focus on self-development early on in their incarceration.

Utilize and regulate clemency

Most state governors have the authority to commute a sentence from life without parole to one that is eligible for parole. The process, though, tends to be highly discretionary, and without guideposts or transparency. Changes to law or regulation can specify a process of review by a parole board or other entity tasked with assessing an individual’s case and rehabilitation, and recommending to the governor those who should be considered for clemency. This ensures a clear, open, and multi-tiered consideration process.